As woodworkers, we use a lot of products containing solvents, like mineral spirits, turpentine, naphtha, and denatured alcohol. The labeling and naming of these products is inconsistent and differs from region to region (note: I’m based in the US, some details below may differ for other regions), so I think it's helpful to understand what each of these products is when deciding about which ones to use in the workshop and what the appropriate level of caution and personal protective equipment (PPE) with each is.

I thought I’d talk about denatured alcohol, which is one of the woodworkers’ most commonly used solvents. This is a bit different than the topics I’ve written about before, but if there is interest, I might write about some other commonly used solvents. I should note that I am an organic chemist who has served as the safety officer for labs I’ve worked in, and to be clear about my biases, I admit I err on the side of caution when handling any volatile organic compounds, so my recommendations are conservative. I also can’t help myself but include some chemical structures in this post, with the intention that they are not necessary to understand this post.

Before jumping into denatured alcohol we should probably define what an alcohol is. This is a point for possible confusion because in chemistry, an alcohol is any molecule containing a hydroxyl functional group, and there are an endless number of molecules containing this functional group (you can spot some of them by keeping an eye out for chemical names that end with “ol,” like methanol and isopropanol). In common parlance, though, alcohol typically refers to ethanol, which is the alcohol present in all alcoholic beverages like beer and wine.

Ethanol is also the main component of denatured alcohol. Ethanol is useful in woodworking because it's reasonably good at dissolving things like shellac, has a low boiling point so evaporates quickly, and must be ingested in large quantities before it becomes toxic. It's the combination of being both a useful solvent and the ability to be ingested as an intoxicant that led to the denaturing of ethanol (i.e., denatured alcohol). Denatured alcohol is ethanol that has been treated to make it unfit for human consumption.

The most common way to denature alcohol is to add a small amount of methanol to it, which is why denatured alcohol is sometimes called methylated spirits. Methanol is an alcohol very similar to ethanol, but minus one carbon and two hydrogen atoms. This small difference makes methanol much more toxic. Methanol’s exact toxicity is a bigger topic than I want to get into here, but for further reading you can check out the CDC NISOH website entry for methanol.

In woodworking applications, exposure to methanol from denatured alcohol happens most often via skin contact and fume inhalation. For myself, I’ve decided not to use anything containing methanol in my workshop because my environmental controls, e.g. exhaust fans or fume hoods (or lack thereof), are not sufficient to control the possible negative effects of repeated methanol exposure. I know for many people their calculus is different. If you do choose to use methanol-containing products, I would strongly encourage you to wear gloves and eye protection when handling and work in a really well ventilated space (and I mean way more than just opening a window).

As an alternative to ethanol denatured with methanol, ethanol can also be denatured with isopropanol. However, at least in the United States, it can be very hard to find. Isopropanol is often used in rubbing alcohol and hand sanitizer and is still considered a toxic alcohol, especially if ingested, but it’s much less dangerous than methanol. For myself, I’m happy to use products containing isopropanol but make sure I’m in a well ventilated space because excessive isopropanol fumes can still be dangerous. And gloves and eye protection never hurt, so I wear those, too.

As an alternative to denatured ethanol you can use ethanol that has not been treated with toxic additives. Pure ethanol or ethanol containing some amount of water are the most common examples. If you search online for ethanol you will get a number of results. Some laboratory suppliers will sell to the general public and have either pure ethanol (usually labeled as something like “ethanol 200 proof, anhydrous”) or ethanol with a small amount of water in it (labeled like “ethanol 190 proof, 95%”). Both options work for woodworking applications with the 200 proof anhydrous (without water) ethanol working better for situations in which you don’t want to introduce any water to the equation. At the time of writing, I could find a one gallon jug of ethanol for ~$85 to $95 depending on if it's 190 or 200 proof. Typically these products have relatively high shipping costs since they are flammable goods (maybe $30-$40). Something to keep in mind for when you’re searching: higher grades of ethanol intended for analytical chemistry can be really expensive, but what I’m quoting above and what is reasonable for woodworking applications is food grade.

There is also a company selling what they call Culinary Solvent, which is just 200 proof pure ethanol. This is the same thing as anhydrous ethanol you would get from a laboratory supplier, so you can compare the cost/convenience of purchasing for yourself. At the time of writing, one gallon of Culinary Solvent is $124 plus shipping.

A potentially easier source for ethanol, as long as some water isn’t an issue for your application, is Everclear 190 proof (or similar products you can find at the liquor store). These food grade ethanols contain ~5% water and are functionally equivalent with regard to woodworking to a 190 proof ethanol from a laboratory supplier.

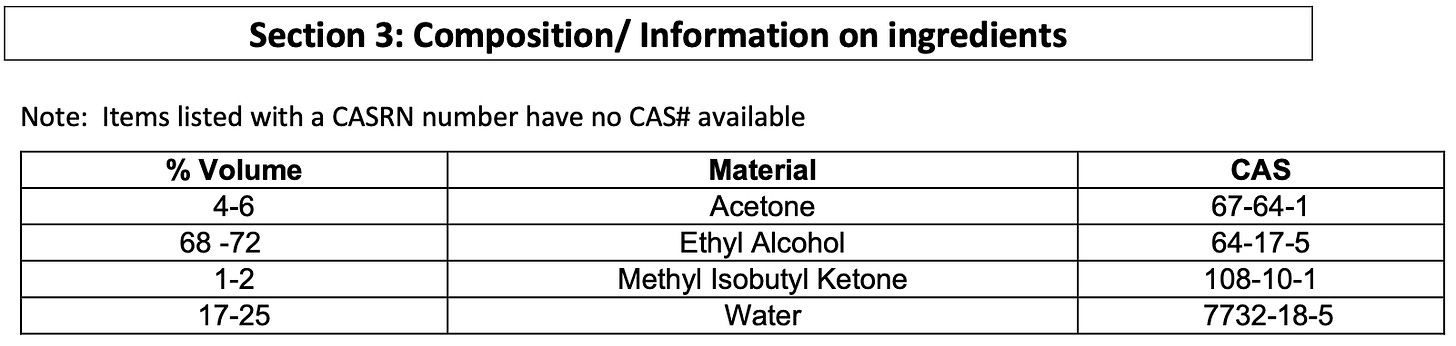

It’s not always easy to understand everything that is in a product labeled as ethanol. If you’re unsure, the best place to check the composition is usually the safety data sheet (SDS), sometimes called the material safety data sheet (MSDS). Typically, section 3 of an SDS will have the product composition. Below, the first example is from a product labeled ethanol 95%. Since the name does not include any modifiers it's mostl likely only water and ethanol, and from the SDS, we can see that is the case. The second image is for a product labeled 70% ethyl rubbing alcohol (remember that “ethyl alcohol” is another name for ethanol). The addition of “rubbing” to the name is a good indication that the remaining 30% is probably not just water. The SDS confirms this: the product is primarily ethanol and water but also includes acetone and methyl isobutyl ketone.

Ethanol comes in many different forms with various additives, which makes buying ethanol potentially confusing. Hopefully, this post made this topic clearer instead of more confusing. If there are other common woodworking solvents you’d like me to discuss, let me know.

I'm a big fan of everclear as my alcohol solvent of choice as well. I don't use it enough the the cost savings over lab-grade is worth it for me.

Also, pure EtOH is hygroscopic and will absorb atmospheric moisture, you'll probably end up pretty close to the same place given enough time (95% EtoH, 5% H-OH) unless you're VERY serious about how you handle and store it.

Thanks for sharing some solid info. I knew denatured was pretty gnarly stuff, but thought only ingestion was the primary concern. One of the few benefits of living in OK is that its easy to get 190 proof ethanol from the liquor store, so its my go to for shellac. It's always fun to read how people's experience outside of woodworking shape/inform their work.